North Polk Teachers and Students Prove Gender Bias Starts in School

Women in Stem

May 27, 2021

Inspiration

After being assigned a topic sheet in English centered around the discrimination women face in STEM, I wondered how female students and teachers in the North Polk School District were affected by this. Discrimination towards females, especially in science-related topics, can start as early as early-elementary school and can travel into the working world. All the statistics that I found showed a fact that is unfortunately not shocking. Women are severely underrepresented in the STEM community and continue to face challenges that their male counterparts often ignore or instigate.

Due to this fact, I was curious to see how many female and male students could actually envision females as a scientist.

To figure out how people in North Polk are affected by this discrimination I decided to do an “experiment” with all grades of the school, as well as interview teachers throughout the entire district.

Scientist Experiment

Even though parents may try to raise a well-rounded and open-minded child, century-old gender norms can be difficult to erase. Young boys are introduced to role models dealing with space travel, activists, athletes, doctors, lawyers, businessmen or officers. Young girls lack realistic role models in their lives; they often read and watch about ballerinas, princesses, and other unrealistic fantasies. With that in mind, it is not surprising that many young girls do not envision themselves or other females as hard-working people, especially within STEM.

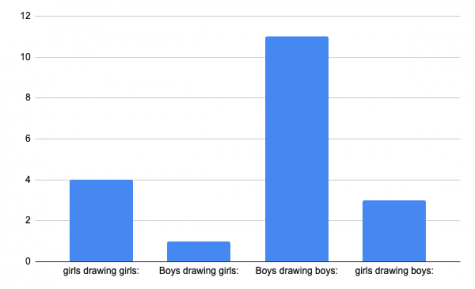

Due to this fact, I was curious to see how many female and male students could actually envision females as a scientist. I asked teachers that taught kindergarten, second grade, fourth grade, sixth grade, eighth grade, and high school to ask their students to draw a scientist. I asked them to give no context to why so that the students would draw what they truly believed to be a scientist.

The findings were predictable, there was only one male student who drew a female out of the 61 male students that participated. Out of the 117 scientists that were drawn, only 28 of the drawings were of women.

The class with the most girls drawing female scientists was second grade, with seven out of 21 students. The least amount of female students that drew female scientists was sixth grade, where three girls out of a class of 23 with 13 girls drew females.

This evidence shows that age might matter. Younger kids are less likely to have a sexist view of the world, whether they’re aware of it or not. As the students get older, the number of females drawn decreases. This proves that sexism is taught as early as kindergarten and drastically changes how children look at the world, and the people around them.

A Difficult Conversation

Ann Bonewitz, Colleen Fowle and Rosalie Eimers have all faced discrimination for being females in the STEM field.

Within the middle school there are only two female science teachers, Bonewitz and Hannah Taylor. In the high school, there are three females out of five science teachers. This includes Eimers, Fowle and Kim Kult.

Through high school, college, and their careers, the female science teachers of North Polk had a long road of difficulties to get where they are today.

Looking back at her high school career, Fowle remembered small instances where she was discriminated against. “In math and science class, I was never really called on. They didn’t call on females.”

It is small examples like those that deter females from STEM at an early age. Because of this fact Fowle is mindful of the people she calls on. Her goal is to get ideas, opinions and answers from all of her students.

Sadly, the inequality she faced only got worse when she moved into college. “Once I got to my third year, I was the only female.”

There is a lot of pressure on females who are in classes with a dominating amount of men. A term that Fowle, and many others use to describe this feeling is called “stereotype threat.” This term is used to describe the feeling of being a minority and walking into a room where you are outnumbered. Even if there is no discrimination within the class, it can still feel daunting just sitting in a room, waiting for something bad to happen.

Fowle describes her experiences in detail. “In graduate school, I took engineering classes at Iowa State. I remember being in a lecture hall of like 75- 80 engineering students and there were three females in the class. That professor, you could tell, he just had preconceived notions about females. He called on us three females when the hardest questions were up, I think to purposely make us look silly in front of the rest of the class.”

Because of the belittlement Fowle encountered, she felt a lot of pressure to excel in the class. “I just felt like every time I stepped in the door of that classroom, I had to be on my game. Basically, I felt like I was representing the whole female gender.”

Fowle was the number one ranking student in her junior class in college yet, she had professors continually tell her that she would not pass their engineering classes, or do well within her STEM career. For this reason, it’s not surprising that the lowest rate of females in any STEM career is engineering.

Going into the workforce Fowle also faced biases. “In the working field I was passed up for a promotion and I was told it was because they needed a strong voice in the room.” Fowle knew that that meant they wanted a man for the position, in a building where all of the higher up people were already male.

These experiences are the reason that Fowle changed her career and moved into teaching. She wants to inspire students from all walks of life to pursue science and make it an inclusive environment.

Unfortunately, Fowle’s experiences are not unique. Bonewitz also faced heavy discrimination in college and in the workforce.

Bonewitz spent four years in college for Biology and chemistry, and two years in professional school for optometry. While in college she, and her female friends, encountered gender based biases.

Bonewitz explained another instance with a friend, “There was also a scholarship that was supposed to rotate, top male- top female chemistry student. When my best friend was supposed to be awarded the chemistry scholarship, which she had outscored the top male by a lot, they still gave it to the male. She got absolutely no help from the head of the chemistry department. He too favored the male student.”

Although her biology and chemistry classes were evenly split with genders, her physics class was 85-15. This is a common trend when it comes to sciences that are considered more difficult and more math heavy.

While Bonewitz’s professors in genetics and biology were always supportive of her and other women to join STEM, her physics and chemistry professors were not advocates for women in STEM. When Bonewitz went back to school for a teaching degree, Bonewitz notes, “I did receive a grant for ‘Women in Science & Math Teaching.’ To help get more women in science and math in secondary schools.”

Teaching is not the only occupation Bonewitz has had. She also worked at Syngenta where she was a team leader for the genetic end of trait conversion.

Bonewitz explains her experience saying, “The agriculture industry is a totally male-dominated industry, you rarely find female breeders. I was Team Leader in the genetics end (lab), but there again, when I was promoted to Team Lead, the males made negative comments, not based on my ability to do my job. If females are placed in top positions in the agriculture business, it is always said they got the job based on the female quota. (They have to fill their quota)- Even though the female is more qualified or better than the male. When females have a strong personality in most science and teaching fields, they are labeled as an alpha female and get negative comments. When males with the same personality are labeled as strong leaders.”

While Fowle and Bonewitz have witnessed and experienced discrimination during college, Eimers had a very different experience when she was in college. “In college, I never felt discriminated against and there were lots of women in my science classes. I went to Iowa State and there were lots of girls taking lots of things for lots of reasons,” explained Eimers.

Eimers also had mostly female math and science teachers, so she was not aware of the biases most women were experiencing.

While she never felt belittled in college or high school, Eimers did face challenges when she started teaching. “When I started teaching and went to science conferences as a chemistry and physics teacher, you’d walk in, and at that point I was in my 20’s, I would think ‘What are all these men doing here?’”

At that point in time, the gap between female and male science teachers was even wider than it is now.

Like most women can imagine, Emiers struggled with the energy that the conferences gave off. “I would be there and a handful, at most, max, five other women. The rest were all men…It was intimidating.”

Eimers personally believes that the vibe you give off to your students determines how they perform in class. If a teacher personally believes that girls are unable to do chemistry, those females will feel less confident in the class. This will ultimately make them perform worse than their male counterparts.

Fowle believes that although percentages of females are going up, many do not go into the working world of their STEM major. “The percentage of females in college who are taking the classes is not that desperate. But, after college they are not choosing to pursue that field…they are feeling that stereotype once they get out into the working world,” notes Fowle.

A large reason for this, is a decision that most men do not have to face. Do women choose children or a career? In the science field, there are very little amounts of part-time work in STEM, and being there for your children is something you can only do once.

The Male Perspective

While the female teachers interviewed could remember their professors, class ratios, and the discrimination they faced, their male counterparts struggled to remember simple facts. They could not remember their class sizes, the genders of their professors or if any of their classmates faced discrimination.

Aaron Dose and Evan Groepper both took STEM classes while attending college. Groepper noted that, like Bonewitz had said, biology classes were typically split down the middle when it came to gender ratios. And many of his professors were female.

Dose added on saying, “UNI in general is more girls than boys anyway. The only STEM class that probably had more males than females was physics.”

In Dose’s labs in college, he remembers that mostly females were the ones usually responsible for writing down notes, instead of their male partners.

Groepper teaches more specific science classes, such as anatomy, where there is a higher amount of females because they want to be nurses, an occupation that is deemed as too “girly” for males to pursue.

Groepper and Dose also never felt any pressure from others to do better in their majors. Dose had a professor approach him about science, the sole reason he is not in communications.

Groepper and Dose are firm believers in making their kids feel comfortable in their classrooms. “My philosophy and tactic in general is that I try to have lots of conversations with lots of kids about things outside of just what we’re doing in class. At the end of the day, I hope that every kid feels like they’re in the room and they’re noticed.”

Groepper also noted that as a district North Polk is becoming more involved with science. “Across the board, an emphasis on science has increased and the female portion of that has increased too.”

While Dose and Groepper create an inclusive environment in their classrooms, they will never know the disparities that their female counterparts face every day because of their career path.

Conclusion

If you asked me to talk about women in STEM a month ago, I would have said something along the lines of, “yah it really sucks that women are seen as unimportant in STEM fields,” and I would have stopped there.

After I had the opportunity to talk to such amazing women who have been through so much to receive the education on a topic that they were passionate about, my eyes were opened. They were opened to the reality that so many people are blind to.

It feels really inconceivable that while our nation and our world is progressing so rapidly around us, that I still have to remind people that sexism exists and is affecting the education of young girls worldwide. The early onset sexism that girls face is erasing so many promising careers, even before a girl reaches the age of 10.

Fowle explains this perfectly saying, “It affects what scientific research is done. If we only have white male voices deciding what gets researched, that’s going to impact our scientific research.”

I feel so honored to have been able to share the stories of all of the powerful women that I interviewed. But I find it very unfortunate that my respect for them grew because of the hate that they have faced. Women do not need to prove their worth through ongoing discrimination to gain anyone’s respect, they gain it through their hard work and determination, like any other person. The world needs to start treating women with the long-awaited respect that they deserve and demand.

L. Moody • May 27, 2021 at 8:55 pm

Excellent article Olivia! North Polk is so fortunate to have such a strong representation of women in the STEM classes for students to look up to.